One of the most common questions I hear is how I got interested in writing.

I actually have a very clear memory of the first story I wrote, based on a dream I had when I was a little girl. I always point to that as the initiation of my interest in story telling. Similarly, when thinking about how I became interested in dance, I remember watching the ballet on TV when I was very young and asking my mother afterwards if I could take dance classes.

Not so long ago, I was asked for the first time how I got interested in science. The question caught me by surprise. It just seemed a strange thing to ask, like “How did you get interested in eating?” Or, “Why do you like breathing so much?”

Unlike writing or dancing, I can’t point to a moment in my personal history when an interest in science began. As far back as I recall, science has always been a part of me. Ever since I became aware of the world, I’ve been exploring and asking questions and trying to understand how things work.

This isn’t something that set me apart as a child. In fact, when you watch how children interact with the world, you realize that with respect to innate curiosity, everyone is born a scientist.

So maybe the question we should ask is not how interest in science begins. Maybe the question to ask is how that interest can be cultivated, nourished, and encouraged to grow – rather than squashed or worse, transformed into hate or fear?

These thoughts were running through my head as I read the story of astrophysicist Jocelyn Bell Burnell, recent recipient of the Breakthrough Prize, one of the most prestigious awards in science.

Born in 1940s Northern Ireland, Burnell had to fight for the opportunity to study science past the age of 12. Even her adult career was an endless cycle of starting over, because the scientific establishment – for all its brilliant minds – couldn’t come up with a way to accommodate women among its ranks.

Yet Burnell not only persisted, she made landmark contributions to her field. Conscious that many of the barriers she faced persist today, Burnell is now using her lucrative prize to establish a scholarship fund for women, under-represented minorities, and refugees to become physicists.

I grew up in a later era, on the heels of the Women’s Movement that battered down the gates that kept us out of so many fields for so long. Through grade school and high school, my interest in math and science was never discouraged. On the contrary, I enjoyed support from my family and a steady supply of wonderful mentors. Being the smart girl in class set me apart and sometimes made me feel lonely, but there was always someone among my friends and teachers to make sure I understood the only thing that mattered was doing what I truly loved to do.

It wasn’t until college, grad school, and beyond that I began to perceive the glass ceiling that still affects many women and other underrepresented groups in the sciences today. Fortunately, by the time I started college I knew what I wanted; I had a strong foundation of self-confidence and the instinct to seek out mentors to support my journey. Still, there were many moments when I considered turning away from this career. I’m glad I stuck with it. Science has been my most constant companion. It’s brought me joy, fulfillment, and what I am most grateful for, autonomy and independence.

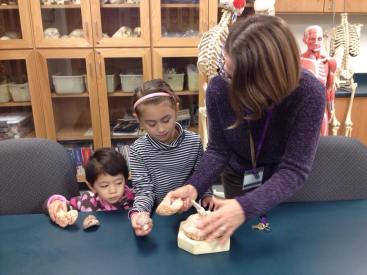

Today I strive to be a mentor in my own right, supporting new generations of students as they start their path toward careers in science. It distresses me to see that even now – even in our own country – bright students with an innate passion for science are turned away from the discipline, often through subtle and insidious means. Implicit bias gets in the way, as does economic background and lack of basic resources and educational opportunities. Sometimes even students who have opportunity find their interests squashed because they end up being bored in the classroom, never making the connection between their innate wonder for life and the power of exploration that science brings.

At a time when it’s more important than ever to recruit people into STEM fields, we need to keep these questions in mind. How do we spark interest in science? And, perhaps more fundamentally, how do we keep innate interest in science alive?

The answers are complex and multi-faceted, impacting students at every grade level and adults at every stage of their career. But if we can remember it’s a natural thing to want to know how nature works, perhaps the rest is just a matter of keeping the flame alive.

2 responses to “Yes, it’s innate”

This should be broadcast throughout every school in the world.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you!

LikeLike